Our Notes & References

First separate edition of this ambitious, relatively early geography of Russia and its new “colonies”, illustrated with a wealth of full-page engraved coats of arms of the Empire’s cities and provinces.

Very rare: we could trace only one complete copy passing through the market in Russia and none in the West; WorldCat lists copies only in four public libraries: Columbia (only copy in the Americas?), National Art Library in V&A Museum in London, TU Darmstadt and Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The young, Tyrol born Philippe Dilthey (also Filipp Genrikh Diltei, 1723-81) was invited to become the first professor of Law at the newly opened Moscow University in 1756. He fairly quickly learned Russian and took great interest in the history and geography of his adopted motherland.

Dilthey published in 1768-78 a 6-volume ‘Atlas des Enfants – Detskii atlas”, both in Russian and French, to present and detail the history and geography of European countries. He dedicated the 4th volume to the Russian empire and had it published separately around the same time as the ‘atlas’ version.

Not only is it the only volume to be published separately, it also differs from the ‘atlas’ version: another title, a preface, a different, much longer dedication… The latter is unusually addressed to 31 distinguished clergymen and 20 governors, in the hope that once they’ve received a copy of the work, they will send Dilthey their corrections, updates and additions regarding the various content of the book, so that he can expand the work into a second edition. Curiously, the title indicates that the work was translated from French to Russian by two military officers, Petr Bibikov and Nikolai Matsnev, while the Atlas’ volume with the same Russian text mentions other names.

The work includes an extensive illustrated description of the coats of arms of the Empire and its districts (including the governorates of Irkutsk, “la Tatarie Russe”, Kyiv, Sloboda Ukraine (Kharkov), Revel (Tallinn) and Riga), discusses some of their main provinces, cities, lakes, rivers, islands and even universities. In his notes about Siberia and Kamchatka, Dilthey highlights: “In 1741, Russians discovered various lands past Kamchatka, in the North American country, and found that the peoples there are very similar to Siberian peoples in housing, food, clothing, and in the faith itself. Therefore, it seems very likely that they have been in contact with each other for generations. It is possible that in ancient times the Chukchi land was connected to America”.

A substantial part of the study is dedicated to the countries “conquered by the victorious weapons of Her Majesty”: Southern Central Europe (Moldavia, Valachia, and the Khan’s Crimea) also including those which “willingly” decided to be submitted to the Empire (the territories of northern and southern Caucasus, from the Black Sea to the Caspian). Dilthey discusses their geography, but also their history, peoples, and economic potential.

Animated with a sort of encyclopaedic ambition, Dilthey adds further details on a wide range of subjects, such as the Christianisation of Rus and the inhabitants of the territory before that, the history of the Russian Church, the Romanov dynasty, the Russian lawmaking presenting its main legislative texts – and he completes his survey with an extensive bibliography: a list of 30 authors who wrote on Russia (most published before the mid-18th century).

Interestingly, Dilthey pays everywhere a special attention to the Lutherans’ and the so-called reformatory’s (Calvinists’) representation in different regions. He notes that the vast Russian land is not everywhere fertile and thus “the wise Empress Catherine the Great populated the empty areas with colonists who were summoned from different countries […] All foreigners have perfect freedom in their faith and enjoy the highest patronage of the Empress”. He also gives extensive details of the famous ‘German colonies’, almost 60 Catholic, Lutheran and Calvinist settlements stretching along more than 300 km on both sides of the Volga from Saratov to Astrakhan. (Dilthey even gives their city of origin, such as Basel, Schaffhausen, Zurich, Lucerne, etc.).

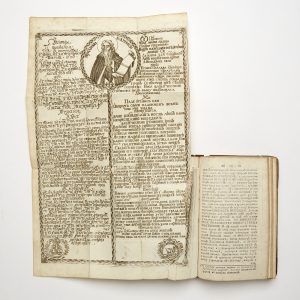

A curious addition to the work is the large folding plate in Greek and Old Church Slavonic commemorating the life and work of Ioannikii Likhud (1633-1717), a Greek Orthodox monk who with his brother Sofronii were the first teachers of the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy, the first official institution of higher education in the Russian state. They were authors of the earliest Russian philosophical textbooks, which contained vast material from ancient and new European philosophy, as well as critique of Catholicism and Protestantism. The text in Greek was written by Sofronii upon Ioannikii’s death and carved over his coffin. Dilthey perhaps resolved to add this plate considering the brothers’ significant contribution to the development of the Greek Orthodox faith and academic education in Russia.

The work ends with Catherine’s order of 4 May 1772 on the establishment of new towns from former villages, which gives an indication about the publication date of both editions (separate and in the Atlas).

Bibliography

Svod. Kat. 1883 and1884; Sopikov 7878; Obolianinov 675; Gennadi, Slovar vol. 1, p. 302;

Dilthey, Philippe Henry // Entsyklopedicheskii slovar Brokgausa i Efrona : in 86 vols, St. Petersburg, 1890 – 1907.

Bolkhovitinov, “Ioannikii Likhud”, Bolshaia biograficheskaia entsiklopediia, 2008.

Physical Description

Duodecimo (16.7 x 10 cm). Engraved frontispiece, [18] ll. incl. half title with French title to verso, Russian title, dedication and preface, 436 pp., with a large folding engraved plate and 33 engraved full-page coats-of-arms lettered A to HH, parallel text in French and Russian.

Binding

Contemporary half calf over marbled boards, spine in compartments with black title label.

Condition

Rubbed, spine especially, with thin vertical cracks; folding plate with closed tear repaired, occasional light spotting or soiling, last page, flyleaves and endpapers with various inscriptions, especially in pencil.