Our Notes & References

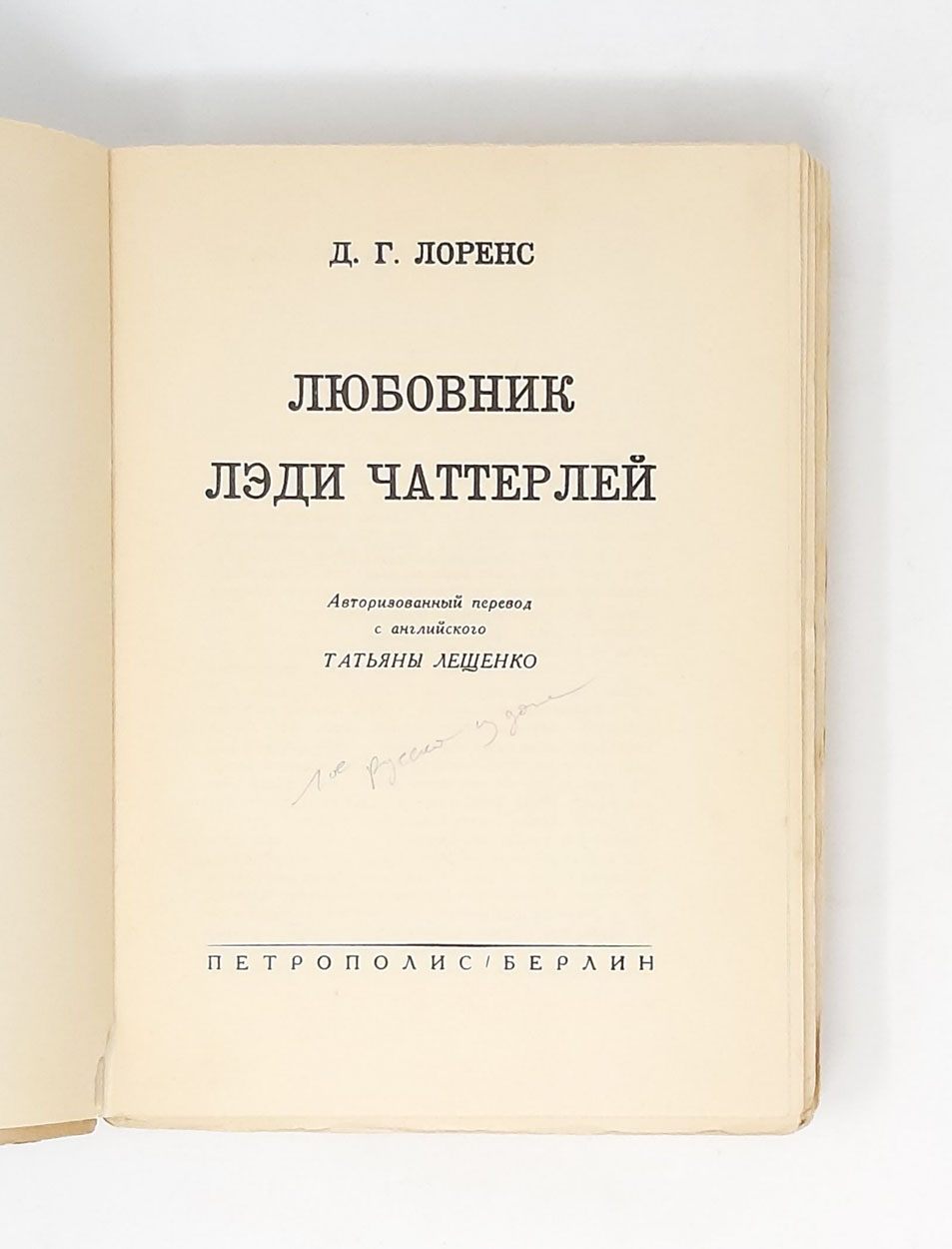

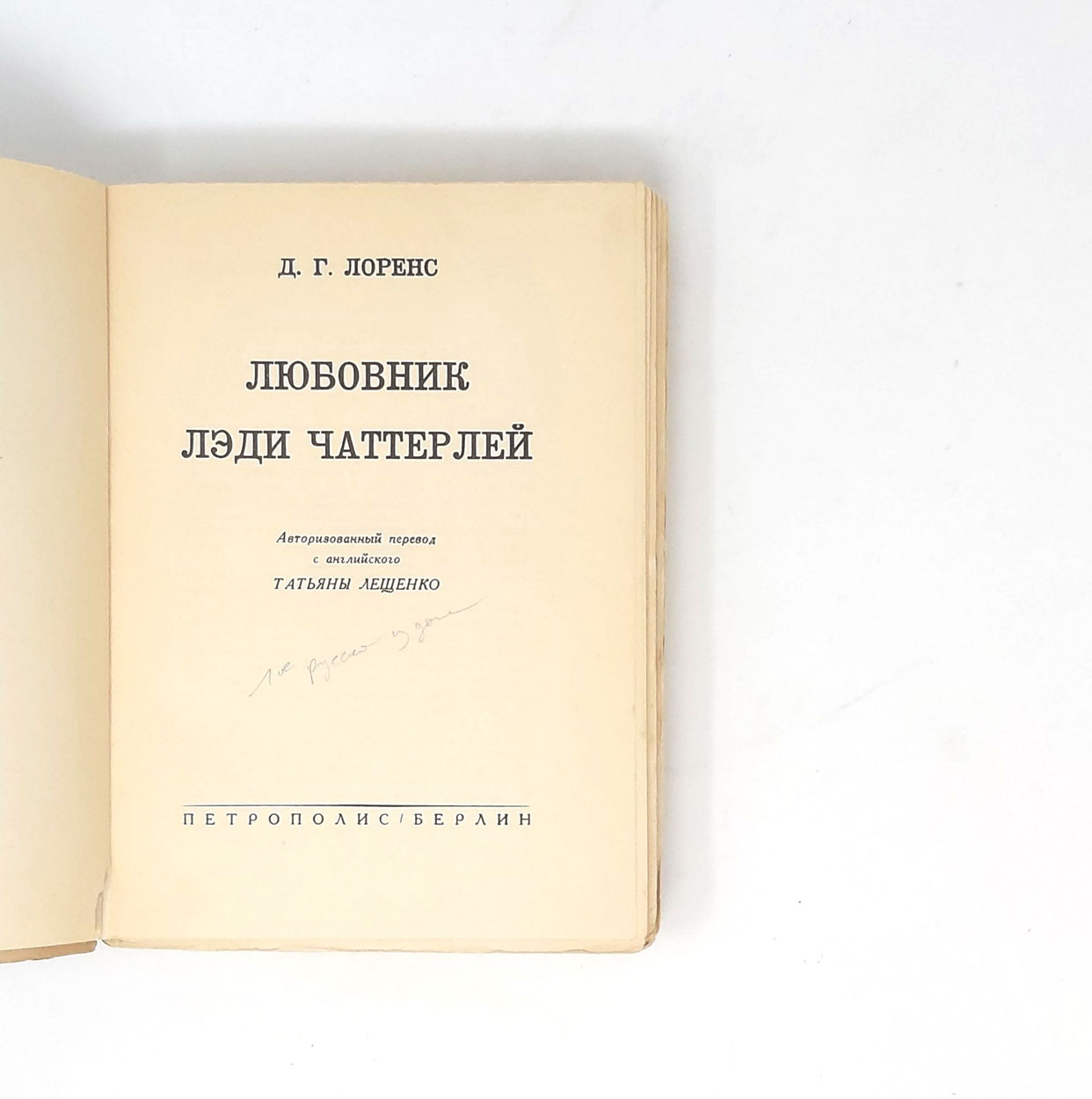

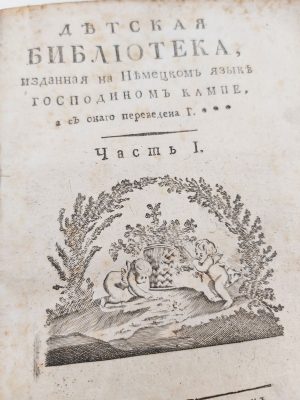

First edition in Russian, “not for sale” and authorised by Curtis Brown Ltd., Lawrence’s literary agents, as stated on the title page verso.

Translated only 4 years after the first edition by a talented Russian woman who went from Moscow to New York and to the GULAG, and inspired Solzhenitsyn.

A book banned in the UK, in the US, and in Soviet Union. Very rare, especially untouched in wrappers: we could not find any copy at auction outside Russia; Worldcat locates only two copies (Princeton, Syracuse). We could not trace any example in Russian libraries, and none in the UK – the BL owning only the 1991 reprint.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover by David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930) joins Ulysses by James Joyce and Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller in the list of the most suppressed book from the first half of the 20th century. First privately published in Florence in 1928, it was immediately banned in England and the US for its explicit sexual scenes and the obscenity in the storyline of the love affair between a working-class man and an aristocrat. It remained unpublished until 1959 when Barney Rosset from the Grove Press won the case in a landmark trial against the novel’s censorship, challenging the US obscenity laws.

This first Russian translation was made in 1932 by Tatiana Leshchenko-Sukhomlina (1903-98), a Russian singer, actress, writer and poetess. Born in Chernihiv, Ukraine to a noble family, she moved to Moscow after the October Revolution and started giving Russian lessons to foreigners coming to the new Soviet Russia. She met there her future husband, the American lawyer Benjamin Pepper, and moved with him to the US in 1924. She graduated from the Columbia University School of Journalism and joined the American Guild of Actors. Soon she divorced Pepper, moved to Paris where she began her career as a translator and returned to Moscow in the 1930s. In 1947, she was sentenced “for counter revolutionary activities” to 8 years in Vorkuta, a town to the north of the Arctic circle and the coldest city in all of Europe. In 1956, she was rehabilitated and continued her translation career, while also gaining popularity as a performer of romances and pre-revolutionary songs.

In The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn mentions Leshchenko among the 257 “witnesses to the Archipelago”, “whose stories, letters, memoirs and corrections were used to create this book” (our translation here and below).

Leshchenko’s translation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was republished in 1991 with a preface and excerpts from an interview she gave to the Soviet-Russian journalist Feliks Medvedev: she recollects some fascinating details about this “great bibliographic rarity” (Medvedev), not for sale and supposedly published in a very limited edition. The divorced Leshchenko was charmed with the book’s “chastity, honesty about love […] protesting against the hypocrisy of English and especially American philistines, who at the time were terribly proud of being sexually chaste”. Since Lawrence died in 1930, she wrote a letter to his executor, the famous writer Aldous Huxley who “welcomed the appearance of his friend’s book in Russian and gave me the right to the authorised translation, confident, judging from the letter that the translation would be excellent”. When the translation was ready, Mikhail Volkonskii (1891-1961), a Russian opera singer, actor, interpreter and a descendant of a famous Decembrist, typed Leshchenko’s manuscript before sending it to the publishing house.

When the book was published, Leshchenko remembers that “One day I came across an advertisement for an event at a club discussing the Russian edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover[…] The large room was packed […] Writers, artists, bohemians. The poet Konstantin Balmont, hunched over and half-drunk, came to mind for some reason. Mark Lvovich Slonim, literary critic, publisher and brilliant personality, gave a [very positive] talk on the book.”

When in the Soviet Union, Leshchenko did not want to mention that she was a translator of such a controversial book and was afraid to give her only translator’s copy to anyone to read. In 1947, she finally lent it to someone but a few months later, she was arrested and her whole library was confiscated. Leshchenko’s copy therefore survived but to the translator’s despair, it was in a terrible condition as the book was secretly borrowed by dozens of other readers while she was in exile.

After Lawrence’s novel was rehabilitated in the English-speaking world, Leshchenko attempted to send the book to the State publishing house Goslitizdat in Moscow. “The publishing house, to my surprise, responded with a kind letter. It was signed, as I now remember, by a director named Kotov. I was informed that Lawrence was socially acceptable to the Soviet reader, that his novel Sons and Lovers had already been published in Russia. Kotov wrote that Lawrence is a former miner, going our way, but the publishing house’s plans for the coming years are full and it is not possible to publish Lady Chatterley’s Lover“. The Russian reader could not officially read the novel until 1990 when the magazine Inostrannaia literarura [Foreign Literature] published the translation by I. Bagrov and M. Litvinova.

Provenance

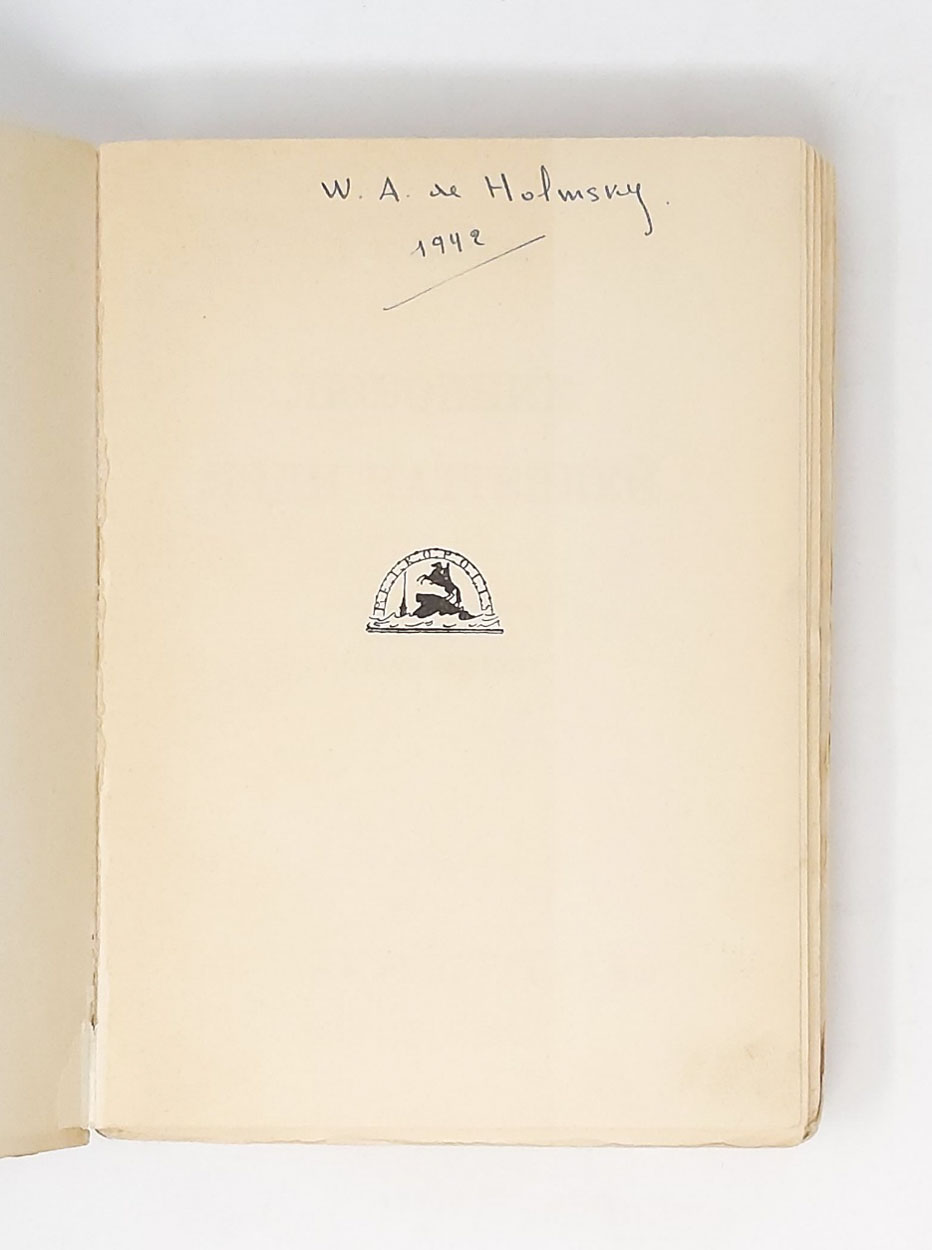

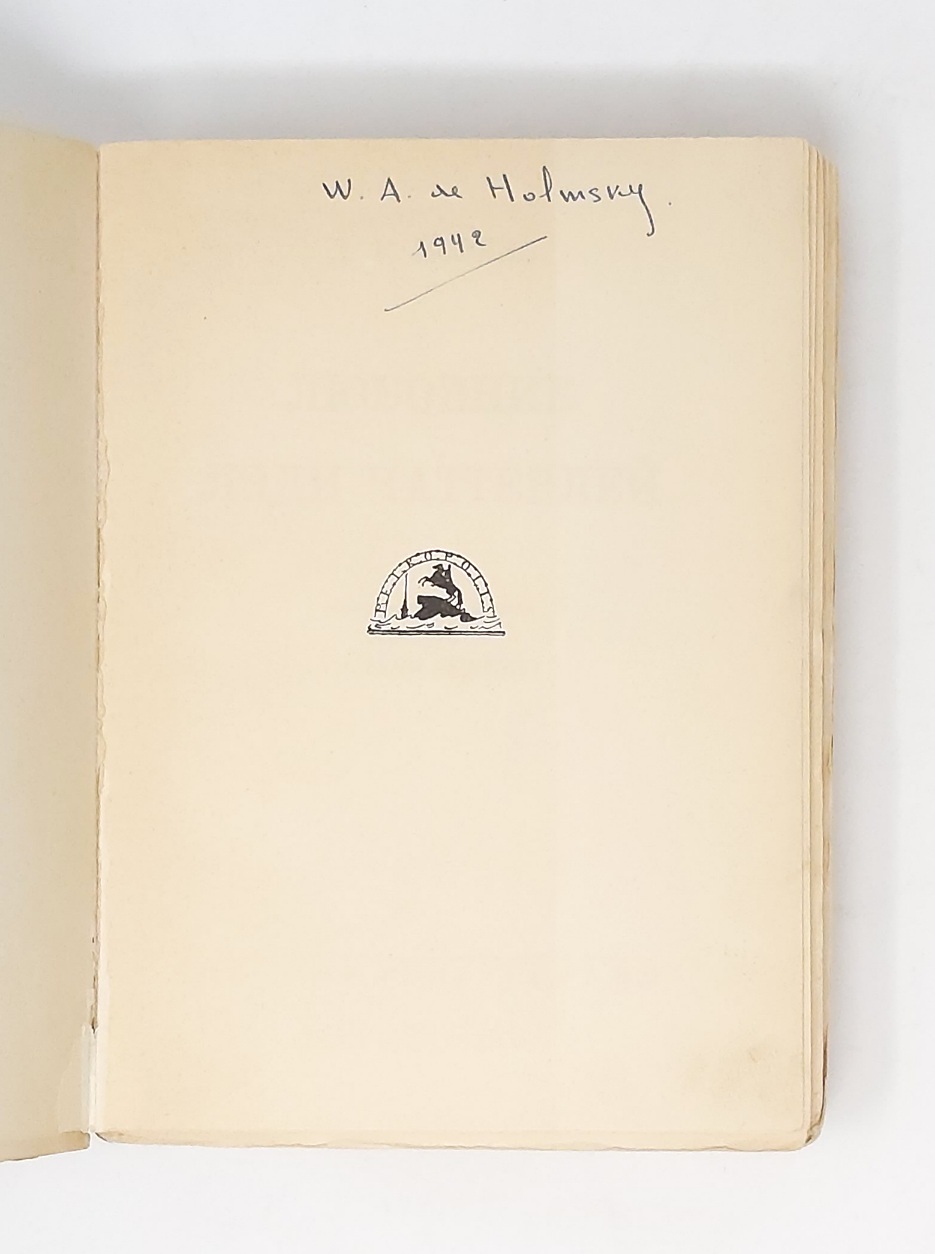

V. A. Kholmskii (Vladimir Aleksandrovich Kholmskii, also Woldemar de Holmsky, 1910-73, émigré living in France from the late 1920s onwards; blue ink inscription to first leaf ‘W. A. de Holmsky 1942’, and in Russian on rear flyleaf ‘V. A. Kholmskii, 1942’; we could trace another émigré work (publ. in 1933) with the same ownership, in the Dom Marina Tsvetaeva, see Russkoe Zarubezhe, Katalog, 1992, num. 6).

Bibliography

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Arkhipelag GULAG. 1918—1956. Opyt khudozhestvennogo issledovaniia. Moskva, AST-Astrel, 2010, Vol. 1, pp. 13, 18.

Feliks Medvedev, “Kniga chistaia, tselomudrennaia…” // D. G. Lorens, Liubovnik ledi Chatterlei, Moskva, Video-Ass, 1990-91.

Physical Description

Octavo (19.8 × 14 cm). 380 pp. including first leaf with publisher’s mark and title page.

Binding

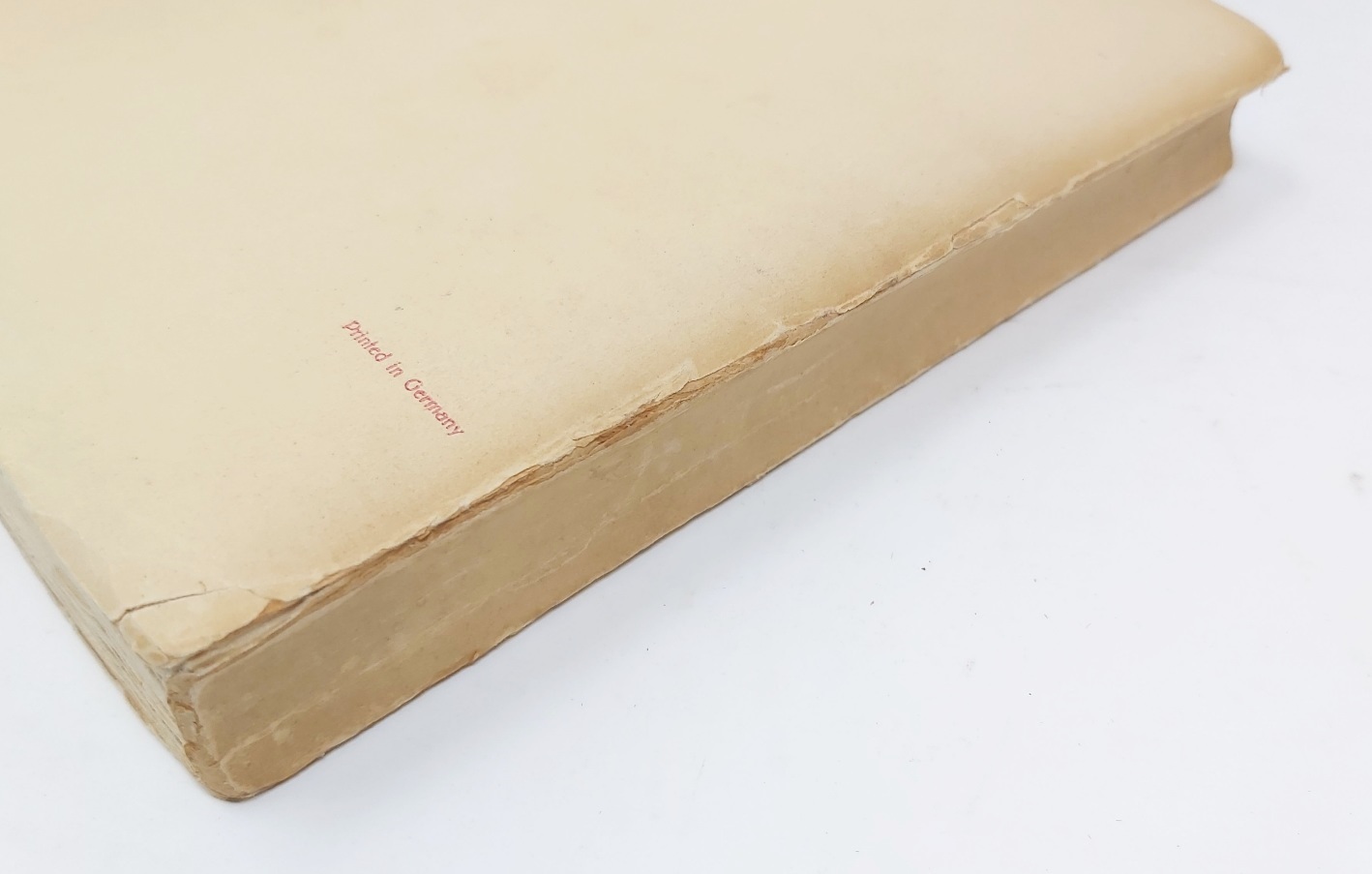

Publisher’s wrappers of thin dust-jacket with internal flaps glued to thicker cream card covers (as issued), lettering in Russian on spine.

Condition

Rubbed and lightly stained, spine evenly discoloured, hinges start to split; first and last page partly lightly darkened and with very minor stains, first leaf with minor tear to gutter, title page with pencil inscription in Russian ‘1st Russian edition’, otherwise clean and fresh internally.