Our Notes & References

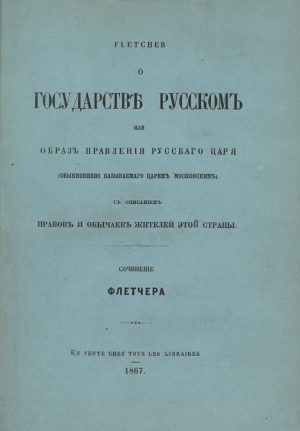

An imperial copy of this major Russian medical work, the first Russian scientific book on the plague and the main source on the 1770-72 plague in Moscow, with a detailed description of the containment measures taken.

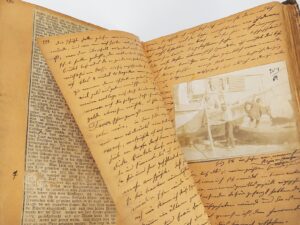

With fine contemporary provenance, then in the Gatchina Palace. “Read in the month of April, 1777, Kositskii” as inscribed on a fly-leaf, with Elfim Kositskii’s elaborate bookplate, representing a rare case of an 18th-century Russian provenance which is not aristocratic. Elfim Vasilievich Kositskii was indeed a merchant based in St. Petersburg (but originally from Kexholm (Keksgolm, and now Priozersk), a northern city on the shore of Lake Ladoga. Also engaged in charitable activities, he gathered an important library of about 4,000 volumes, mainly of 18th-century works, which he then donated to the St Petersburg University in the 1820s.

This particular volume integrated the ‘Gatchina Orphanage Institute of Emperor Nicholas I’: founded in 1803 on the initiative of Empress Maria Fedorovna and first called the Gatchina Foster Care Home it was located right next to the Imperial Gatchina Palace. It became the Gatchina Orphans’ Institute for Boys in 1837, renamed again in 1855, and functioned as an orphans’ institute till 1917.

The volume however left the Institute earlier, to join the extensive library of the palace itself. Built in 1766-81 for Catherine II’s favourite, Count Orlov, this important palace was purchased back by the imperial family upon the Count’s death in 1783 for the future Emperor Paul I and his wife Maria Fedorovna (who had both a superb library). Gatchina became later a regular residence of Emperor Alexander III. The library collections of these monarchs formed the core of an extensive Palace library enriched over time with other collections from the royal family members and institutions, including the Gatchina Orphans’ Institute.

Very rare: we could trace only one copy in public institutions outside Russia (the Yudin copy in the Library of Congress); not in the Wellcome nor the NLM. We could trace 4 copies in Russian libraries (RSL, Pres. Library and 2 in the NLR), and we handled another one, now in a private collection.

An important work on disease control and prevention

Shafonskii was at the heart of the bubonic plague outbreak in Moscow in 1770 and instrumental in its suppression. Originating in the army, the plague spread to a military hospital in Moscow where 27 patients fell ill and only 5 survived. Shafonskii was the first to recognise it as the plague and quickly warned his colleagues, many of whom dismissed him as causing unnecessary panic. Rinder, a German doctor who was in charge of public health for Moscow chose to ignore him and continued to do so until 1771 when he died of the disease himself.

At the epidemic’s peak a thousand Muscovites were dying a day and the Governor, Petr Saltykov along with three quarters of the population fled to the Strict regulations were brought in with shops, taverns, factories and even churches being forced to close. People were stripped of their livelihoods and infected houses were burnt down. Cases were rising and so was public frustration, with many people being suspicious of the reasons behind emergency measures. When Archbishop Ambrose removed an icon for hygiene reasons a mob descended and murdered him, brandishing him an ‘enemy of the people’.

Catherine the Great was hesitant to publicly acknowledge the outbreak but as the situation deteriorated she sent her lover Grigorii Orlov to restore order (either because she trusted him or wanted to get rid of him). Orlov, who worked closely with Shafonskii increased the use of quarantines, travel restrictions and ‘social distancing’ measures. 18th century PPE including mittens and masks were required to be worn and long poles were used when burying the dead. Bank notes were soaked in vinegar before being handed over to tradesmen and cemeteries were moved outside of the city walls.

To encourage people to go to hospitals if they fell ill, financial incentives and clothes were handed out by the authorities. A sizeable figure of 10 roubles was offered to married couples who voluntarily admitted themselves. This did, however, cause many to lie about whether they had any symptoms. The state rewarded doctors with a bonus and looked after every homeless person on the streets. A strict 6 week quarantine in special houses was upheld before anyone could travel to Petersburg and compliance with medical regulations was mandatory. These sustained efforts meant a return to normal life was possible and Shafonskii was able to write this work and advise how best to avoid another outbreak. Medical interest in the epidemic was piqued in Western Europe with An account of plague which raged in Moscow 1771 being published in 1798 in Latin by Belgian physician Charles de Mertens; an English translation was released in 1799.

Shafonskii argued that precautions must be taken to ensure such a scenario did not happen again. These included quarantining troops upon their return from foreign campaigns, regulating trade routes from Europe and Turkey into Russia, increased sanitation of hospitals and factories and forceful punishment of those not adhering to the rules (including those digging up dead bodies). The plague of 1770-1772 had shown that intense organisation of state establishments and medical committees was needed to combat the outbreak and quell the threat of public disorder. With the stringent rules in place the outbreak was relatively short, aided also by the freezing winter temperatures killing off bacteria.

Shafonskii’s thick work, illustrated and containing valuable contemporary documents, was preceded in Russia only by two books on the plague: one published in 1656 by Patriarch Nikon considering the religious aspect of the pandemic, and a small volume published in the waked of the Moscow plague, in 1772, a translation from the German of Richard Mead’s 1720 A Short Discourse Concerning Pestilential Contagion (also known as Discourse on the plague).

Provenance

Elfim Vasilievich Kositskii (his bookplate to upper fly-leaf and his inscription to lower fly-leaf); Biblioteka Imperatorskago Gatchinsk. Nikolaevsk. Sirotsk. Instituta (Gatchina Orphanage Institute of Emperor Nicholas I; post-1855 shelf label on upper pastedown and spine, ink stamp on title); Gatchinskii Dvorets (Gatchina Palace; ink stamp with shelf number inscription in black ink on verso of upper flyleaf).

Bibliography

Berezin II-198 (“rare”); Bitovt 1841; Smirdin 4798; Svod. Kat. 8222 (illustrated); for Kosiotskii provenance: Ivask, p. 158, b) (Kostiskii) and p. 142 (Gatch. Insti.).

Physical Description

Thick 4to (25.2 x 20.5 cm). Title, [6] dedication, VIII preface, [8] t.o.c, 652, [3] pp. errata, with 2 folding plates.

Binding

Full contemporary marbled tree calf, spine with raised bands, red and light-brown morocco labels with gilt lettering in Russian, gilt fleurons in compartments, red edges, decorative gilt fillets on board edges, marbled endpapers.

Condition

Binding a bit crackled and lightly scratched, board edges, head of spine and upper hinge skilfully restored; rare spotting, a few leaves lightly browned, small stamp “printed in Russia” glued to title; an attractive, crisp example.

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #2](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_1.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #3](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_2.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #4](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_3.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #5](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_4-scaled.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #6](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_5-scaled.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #7](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_6.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #8](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_7.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #9](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_8.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #10](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_9.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #11](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_10.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #12](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_11.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #13](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_12.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #14](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_13.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #15](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_14.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #2](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_1-300x347.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #3](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_2-300x400.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #4](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_3-300x274.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #5](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_4-300x225.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #6](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_5-300x225.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #7](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_6-300x361.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #8](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_7-300x225.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #9](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_8-300x245.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #10](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_9-300x400.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #11](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_10-300x209.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #12](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_11-300x400.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #13](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_12-300x225.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #14](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_13-300x400.jpg)

![Image for SHAFONSKII, Morozovaia iazva [Description of the Plague]. First edition, Moskva 1775, Imperial copy. #15](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2237_14-300x400.jpg)