Our Notes & References

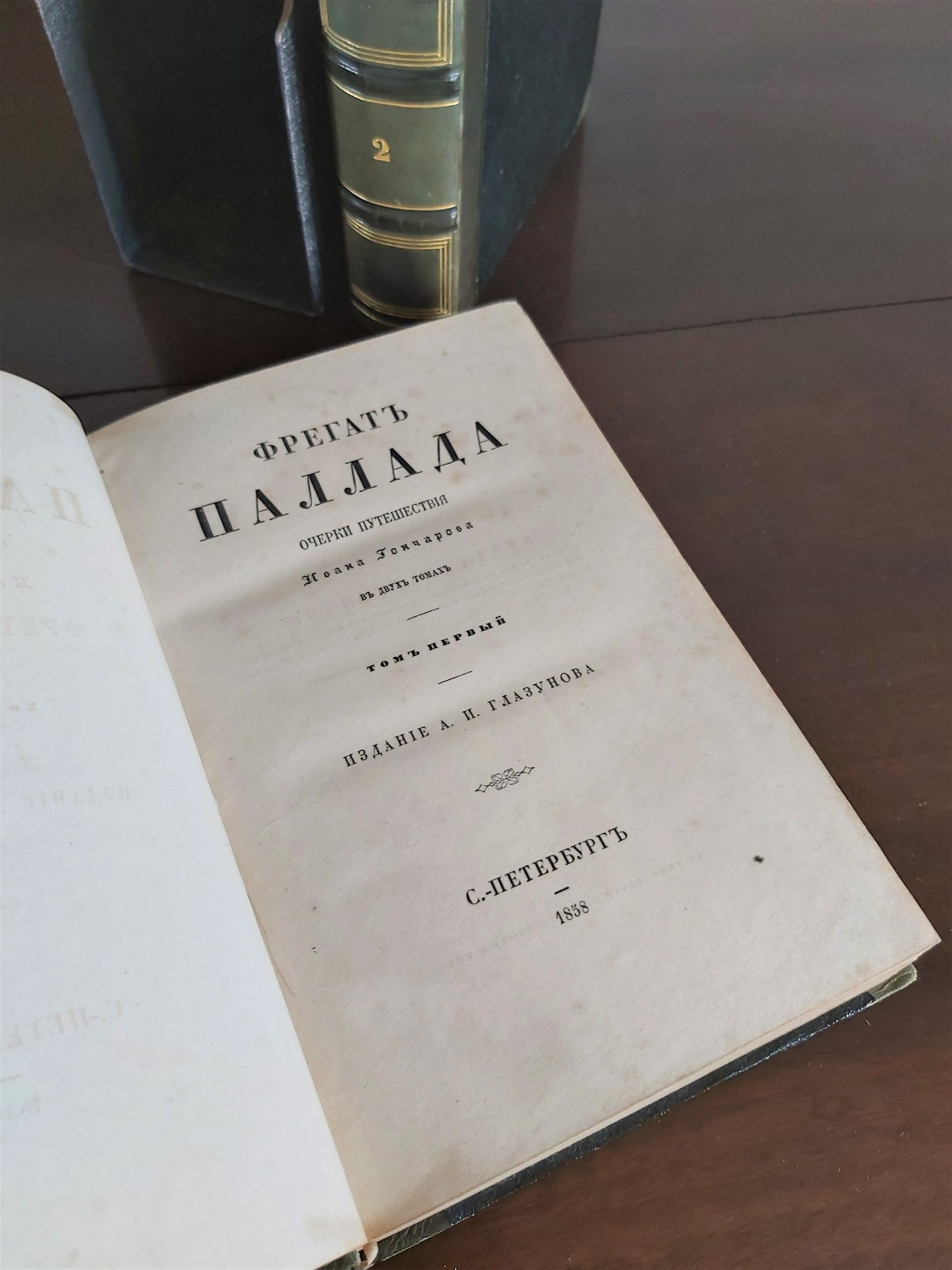

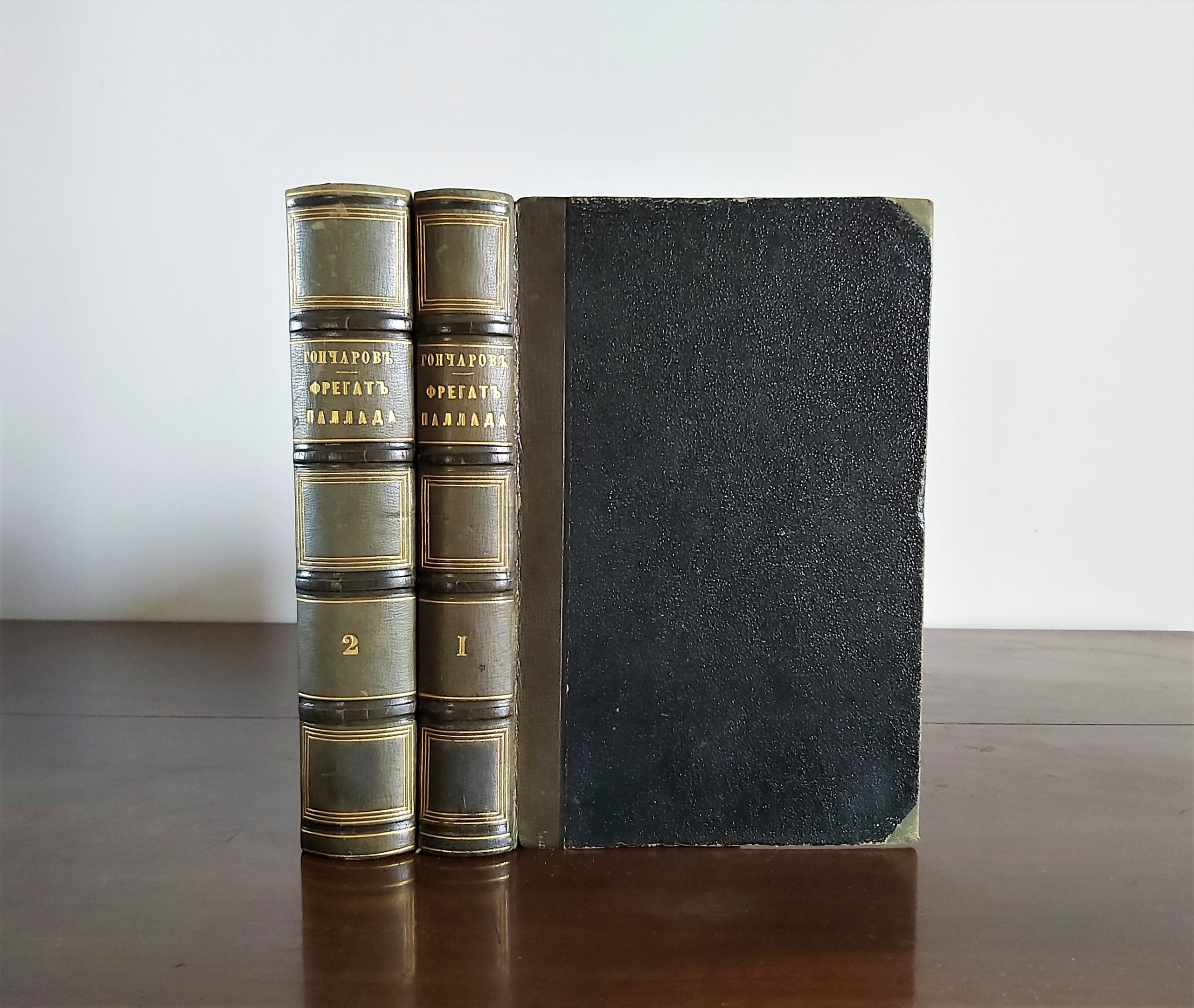

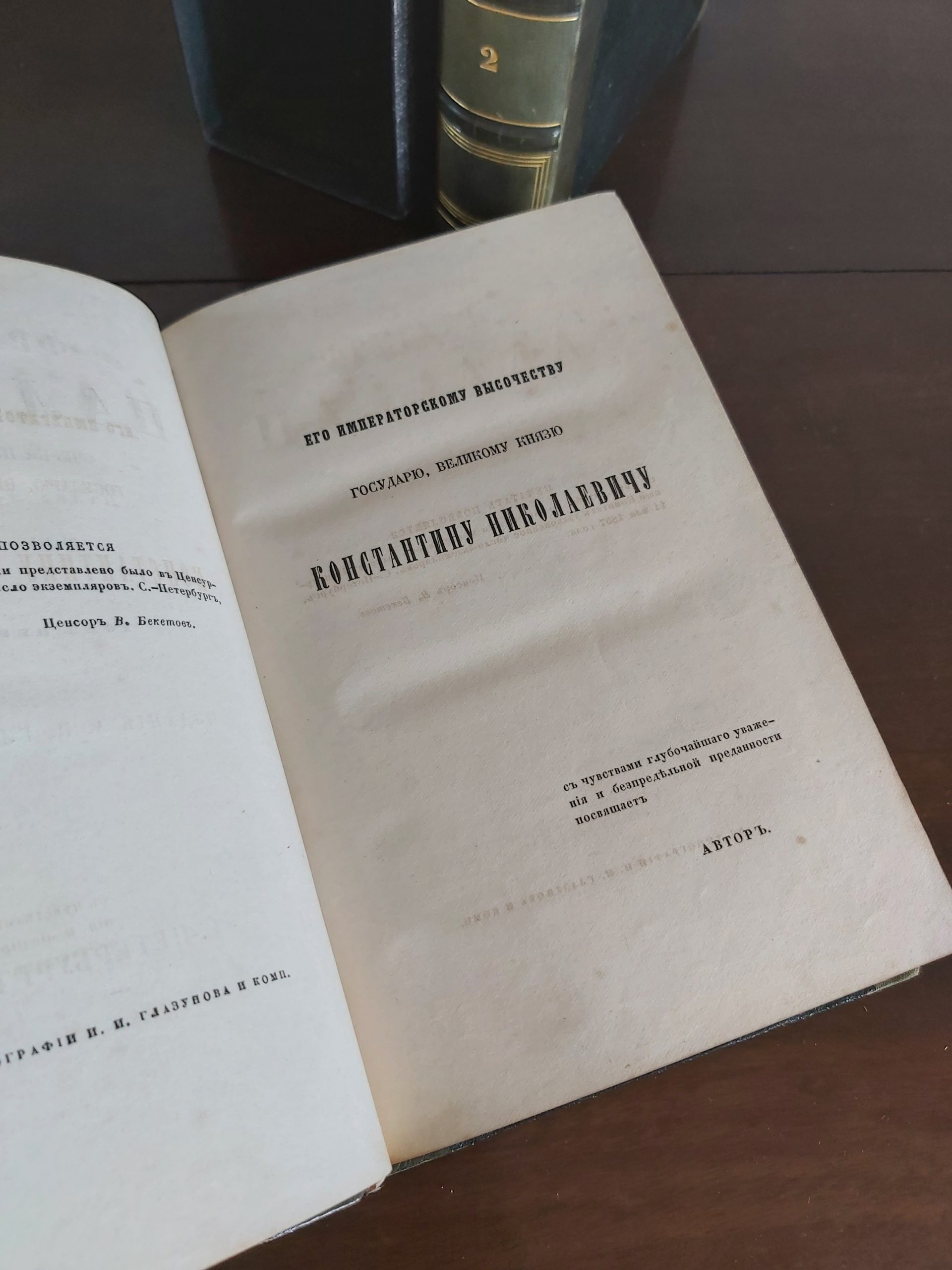

First book edition of Goncharov’s travel account describing Count Putiatin’s expedition to Japan: a lovely example in an attractive contemporary Russian binding.

While writing his masterpiece novel Oblomov and before publishing it, Goncharov (1812-91) joined Putiatin’s expedition as a secretary in October 1852, on board the frigate Pallada. After almost 2 years, he left the frigate in August 1854 and took 6 months to go back to St. Petersburg by land, while Admiral Putiatin went back to Japan to sign the Treaty of Shimoda in Februrary 1855, just when Goncharov was approaching St. Petersburg. This landmark treaty was the first between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan, which, together with the Convention of Kanagawa between Japan and the United States (1854), ended Japan’s 220-year-old policy of national seclusion.

On board of Pallada, Goncharov’s duty was to keep the ship’s log-book: this served as a basis for his important travel account.

A first excerpt of Goncharov’s notes, titled “Likeiskie ostrova” (Liuqiu, or Ryukyu, Islands of Japan) was published as early as April 1855 in the journal Otechestvennye zapiski [Notes of the Fatherland]. Other excerpts would follow, in various literary or maritime periodicals, sometimes accompanied by a subtitle, such as “From Traveling Notes” or “Chapters from the Diary”. The full work was published only in 1858, as a two-volume book presenting the complete text for the first time – but also for the last time in a while. Indeed, Goncharov took out some details in later editions, in particular descriptions of local cuisines, which his contemporaries found irrelevant.

Goncharov’s notes comprised partly his diary entries, partly his letters to friends and fellow writers. He filled his letters with direct observations, intending to use those in the final publication. He eventually kept the full letters in his publication, preserving the epistolary, impromptu nature of the work and also making it an important literary source, the earliest version of the full work, as the original manuscript has been lost.

As a result, this first edition gives a sincere, unedited account of how a Russian 19th-century intellectual reacted to seeing the natives of Africa and Asia for the first time. Here, anecdotes about eating bananas for the first time (in Madeira – Vol. I, p. 143) or trying curry in Cape Town (Vol. I, p. 225) and ‘saki’ in Japan (Vol. II, p. 247) appear side by side with a serious analysis of the British imperialism (Vol. I, p. 221) and of the ultimate feasibility of colonial presence in South Africa.

After detailed observations and thoughts on Africa, Goncharov also captures European perceptions of the multi-cultural world of South East Asia. In Singapore, he encountered three cultures previously unknown to him: indigenous Muslim Malays, Hinduist Indians, and Chinese immigrants. He describes the process of rapid economic growth in Singapore, which started after the island had become a British possession in 1824. The cultural mosaic is captured on many levels, including the diversity of local dwellings (Vol. I, p. 427).

Arriving later in Hong Kong, Goncharov describes this relatively recent British colony, with its early English settlements (p. 461) and the exodus of Chinese workers from the Portuguese colony of Macao and their relocation to Hong Kong (p. 466). He also makes a rare reference to the activities of Jardine, Matheson & Company (currently Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited), the British firm which emerged in 1832 and later set up its headquarters in Hong Kong and grew rapidly.

Japan is at the core of the second volume: it contains unique, detailed accounts of the Russian negotiations. Although Goncharov personally suffered through the long month of August 1853 while waiting for an audience with the governor of Nagasaki, he described Japan as dreamlike:

‘What it is? decoration or reality? what a terrain! The nearby and distant hills, one greener than the other, covered with cedar and many other trees […] crowd like an amphitheatre, one above the other. There is nothing scary, only smiling nature: perhaps, behind the hills, there are laughing valleys, fields… But […] one cannot think that people smile very much among these hills. All mountains are ridged with furrows and cultivated from top to bottom’ (p.10, our translation).

Everything interests Goncharov: harakiri (or seppuku), a Japanese ritual suicide (p. 68); Japanese calligraphy (p.24); Japanese chopsticks and food (p. 78), etc. After a month of tiresome negotiations, Goncharov began longing for the Russian snow, but before his return to Russia, the expedition had to go through Shanghai, Liuqiu Islands, Manila, Kamiguin in the Philippines, and the Korean Port Hamilton: many foreign lands which Goncharov describes in his notes, finding constant opportunities to compare them with his native Russia. This is one of the reasons why Fregat Pallada was crucial for his development as a writer: Goncharov’s new knowledge about nations of the world enabled him to develop his idea of the Russian national character in his next novel, Oblomov.

The work closes with three chapters covering his long return through Siberia, focusing especially on the Far East and Yakutia, with the same degree of acute and intelligent detail – amazed to have “Forty degrees of frost. – Frozen wine and cabbage soup”.

Responses to the book edition of Fregat Pallada were mixed, as some of Goncharov’s observations were ahead of his time. While the newspaper Severnaia Pchela (1858, No. 102) congratulated the “educated Russian public” on the appearance of a “smart, entertaining, generally useful book”, a radical Russian writer Dmitrii Pisarev noted in 1859, with regard not only to Fregat Pallada, but also to the newly published Oblomov, that Goncharov “did not care about the big absurdities of life; microscopic analysis satisfies his need to think and create” – Pisarev also admitting that as an artist and an observer, Goncharov “deserves all praise” (Goncharov, p. 533).

Bibliography

Kilgour 358.; Bozovic, Marijeta, [Oblomov and the Grand Tour: Edifying Travel and How We Read Goncharov’s Novel] Bol’shoe puteshestvie Oblomova: Roman Goncharova v svete prosvetitel’noi poezdki. In Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie [New Literary Review] 106 (2010): pp. 130-145; Goncharov I. A. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii i pisem v 20 tomakh [Complete works and letters in 20 vols], ed. T. Lapitskaia, V. Tunimanov. St. Petersburg: Nauka, 2000. V. 3, pp. 393-829.

Physical Description

Two volumes large 8vo. Half-title, title, dedication leaf, I-VI publisher’s preface, I-III t.o.c, 500 pp.; half-title, title, I-IV t.o.c, 659 pp.

Binding

Contemporary Russian olive half-calf over black pebble-grained paper, olive cloth corners, spines with raised bands with gilt lines and direct gilt lettering in Russian, silk bookmarks. Kept in a cloth slipcase.

Condition

Binding lightly rubbed at edges and hinges, spine very lightly discoloured, lower compartments a bit restored in their centre, USSR Goncharov postal stamp to upper pastedown of volume 1. Block a bit toned, rare pencil markings or marginal staining, occasional light foxing, a bit more pronounced on a few leaves of volume 1. Overall though a very well preserved example.