Our Notes & References

A most unusual item: a fully lithographed roll of almost 10 meters detailing and illustrating instructions for the pompous funeral of the monarch.

Very rare: Worldcat locates only one copy, in Dresden (Universitätsbibl., apparently as leporello and not roll), and we couldn’t trace any copy in the major Russian libraries, nor in the usual bibliographies (not in the Russica catalogue in particular).

The hero of the victory against Napoleon, Tsar Alexander I of Russia died on 12 December 1825 in Taganrog; on 29 December, that is, 40 days after the death, the funeral train with his body departed from Taganrog to St. Petersburg through Ekaterinoslav, Ukraine, Kursk, Orel, Tula, Moscow, Tver and Novgorod. On 3 February 1826 the procession arrived in Moscow to take a long stop to organise the farewell ceremonies. On 28 February, the coffin arrived in Tsarskoe Selo, from where a week later it was transported with due honours to the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Then on the 13th of March 1826, during a heavy snowstorm, the body was finally transported to the Peter and Paul Cathedral for burial.

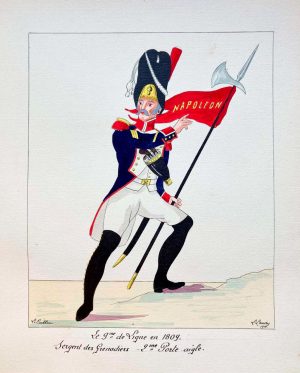

Given the use of the future tense in the text, these instructions must have been printed sometime while the coffin was en route to St Petersburg, possibly by Pluchart in that city, as he was the most advanced lithographer in Russia at the time. He actually published, after the event (censor’s note dated 22 April 1826), a visual panorama of the funeral: also very long, this ‘Cortège funèbre de feu S[a] M[ajeste] L’Empereur Alexandre I-er, de glorieuse mémoire’ was fully lithographed too, but showing the participants’ profiles and with a minimum of text. This presentation is much more usual for such a work than our ‘Procession funèbre’, where the text is abundant and the numerous illustrations resemble rather simple sketches, showing the participants from behind. Formed of 17 narrow sheets of paper joined in a long lithographic roll on a wooden spool, the work was most likely intended for a limited number of viewers, and appears to be much more unusual as a preparatory document than, for example, the ‘Programme du cérémonial…’ which was printed at the same time. It is possible that our scroll is a French translation, or perhaps adaptation, from some Russian ‘Tseremonial’.

The plan for the funeral procession is structured on fourteen sections. Each section is presented in two vertical parts: on the left is the representation of people seen from behind (on horseback or on foot with ordinary soldiers represented by dots), and on the right are the titles and functions of each person. The procession opens by the prestigious Preobrazhenskii Guards Regiment, followed by the drummers and trumpeters of the Cavalry Guards, then the banners of the empire’s subjects: “on either side of each horse hung shields bearing the coats of arms of the various provinces of Russia and its dependencies, one coat of arms per horse; a black cloth entirely covered each animal and extended two yards behind it, supported by two pageboys” (from the letter of an employee of the British embassy Mr. John F. Kennedy, quoted by Bulanin; our translation here and below).

The following sections include various representatives of the bourgeoisie and merchants, the nobility and officials; then the North American Company, the Economic, Charitable and Prison Societies, followed by the officials of the Imperial Foundling House and other institutions under the patronage of the Dowager Empress-Mother Maria Feodorovna. The next section is headed by officials of the Court Office, the Cabinet, the ministries, the Senate, and the State Council. The clergy precedes the funeral chariot, the Emperor, the Empresses and the Imperial family. “The gilded funeral chariot was topped by a tall hearse. The coffin proved too heavy for the adjutants, and so it was carried by about twenty soldiers to the church and up the steps of the hearse prepared for it, tastefully arranged like a miniature pagoda” (John F. Kennedy). At the end of the procession, the company of the Emperor of the regiment of the guard of Semenovskii is pictured drum beating the funeral march. Finally, come instructions on the start of the procession, the set-up and the general course.

Anne Disbrowe, the wife of the British envoy to Russia and famous for her letters, was anticipating the tsar’s funeral in the following terms: “The arrival of the body at the Kazan Church is expected on Saturday. We ladies of the diplomatic corps have a special invitation; it will be an extremely tedious enterprise. We are to assemble at the church at nine o’clock and remain on the porch until the arrival of the body, after which we are to follow it inside and stand until the end of the service. I think we should not get home before four o’clock. My greatest fear is the cold, as we are not allowed outer garments, of course, and will have to stand under the colonnade for a long time […] The whole corps will assemble at the French Ambassador’s, and from thence ride out accompanied by a cavalry escort. We are given strict orders to leave our lodgings securely closed and under guard. Every precaution is also taken to prevent disturbances. Sixty thousand soldiers with loaded guns will be on standby just in case, though I am confident that all will pass off peacefully” (quoted by Bulanin).

Provenance

Miss Wilmot Horton (perhaps daughter of the British politician Sir Robert John Wilmot-Horton (1784-1841); gift inscription to verso).

Bibliography

Dmitrii Bulanin, Podlinnye pisma iz Rossii. 1825-1828, “Pokhorony Aleksandra v pismakh semi angliiskogo posla” SPb, 2011. pp. 99-105; Marina Logunova, Pechalnye ritualy imperatorskoi semi, Tsentrpoligraf, 2011.

Physical Description

Lithographic roll (6.7 x 915 cm) on 17 conjoined paper sheets, on a wooden spool, printed in black on beige paper.

Condition

Some browning and marginal chipping at start, affecting a few letters of title and first section, a closed tear skilfully restored at beginning, another one further in the text anciently backed with linen, otherwise in appealing condition.

![Image for Procession funèbre [...] du corps de feu l'Empereur Alexandre I. Lithographed roll, first edition, 1826. #2](https://www.pyrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2459_1.jpg)